There are no missing zeroes: that’s just how small of a number it really is. Thankfully, castoreum use in food and beverage production (and, even, in perfume production) is so small as to be practically negligible: while vanillin production is at around an average 18,000 metric tons annually, castoreum is produced at around an average 292 pounds annually. However, the substance that is harvested is completely safe for human usage, which is why the FDA constantly marks Castoreum as generally safe for consumption. Yes, that sentence is just as gross as the actual process. During the 20 th century, scientists figured it’s easier, most sustainable, and slightly less cruel to just anesthetize the animal and “milk” the anal sac. Before the 20 th century, people would just straight-up murder a beaver, cut out the anal sac where the castoreum is stored, and just squeeze it out from there. Here’s the thing: castoreum is a pain in the butt (pun intended) to harvest. If it was something that manufacturers used, it wasn’t a practice that was kept up, and for good reason: castoreum is ridiculously expensive. After all, unlike hydrogen sulfide and despite its gross origin, castoreum is actually very pleasant to smell, so why wouldn’t food manufacturers use it to boost their vanilla tastes?īut did they ever? Older food manufacturers around the world deny ever using castoreum, but some people posit that it may have been used back in the early 20 th century, albeit sparingly. To be more specific, castoreum is a yellowish-brown, sticky and unctuous substance that is known for its strong, pungent odor that is, strangely enough, extremely reminiscent of vanillin.Ĭastoreum has had a long history of usage as an additive to perfume, dating back all the way to Roman times, so scientists figured “hey, why not add it to food?”. In 2013, National Geographic ran a story about castoreum and how it’s an extremely pungent substance that is secreted from the beaver’s anal sac as a way for them to mark their territory. One of the components they stumbled upon was castoreum, a type of chemical that is derived from, well, beaver butts. Over the course of a few decades in the early 1900s, scientists were experimenting with different combinations of both organic and artificial ingredients to create vanillin. Does Vanilla Flavor Come From Beaver Butts? No, literally: over the past few years, manufacturers regularly produce about 18,000 metric tons of artificial vanillin, with around 85% of that being made from guaiacol-derived vanillin.

While the exact formula is complicated, it was simple enough that manufacturers began pumping out artificial vanillin by the boatloads. Vanillin was artificially synthesized through a combination of lignin, clove oil, pine bark, and rice bran, among other things. Where Does Vanilla Flavor Come From? The Complicated Answer Photo by Dovile Ramoskaite on Unsplashīy the early 1900s, scientists were able to extract vanillin, the “flavor” that we perceive as vanilla, from the vanilla plant. Thanks to the Albius method, however, plantation owners around the world were able to recreate the Mexican plant’s success, with Madagascar becoming a vanilla powerhouse in the mid-18 th century.īy the late-1800s, vanilla had become an important produce that chemists in Europe and America, daunted by the expensive export and production fees, began looking for alternatives. To understand why extracting “real” vanilla flavor is so difficult, we have to go back all the way to the early 1800s, when a young slave boy in the French colony of Réunion, Edmond Albius, created a method of hand-pollinating vanilla flowers in such a way that it yielded exponentially more than traditional wait-and-see methods.īack then, the vanilla plant had only been cultivated successfully in the New World, specifically Southeastern Mexico, where the plant is endemic. You read that right, but we’ll get to that later in this article.

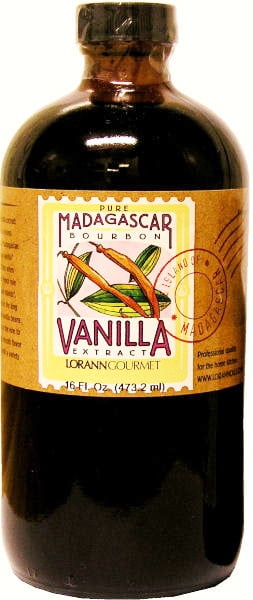

Rising in some information that the vanilla flavor we consume today actually comes from a beaver’s butt. In fact, roughly 5% of all food and drinks produced in the United States contain some form of vanilla flavoring, while around 18,000 food and beverage products around the world carry the term “vanilla” to describe its taste.īecause of how often it’s used, deriving all-natural, organic vanilla flavoring is exceedingly difficult. While that answer might sound sarcastic, it actually isn’t: by and large, the flavor that we understand to be ‘vanilla’ comes from the plant that it’s derived from.īut here’s where it gets tricky: vanilla is used in such a wide variety of foods that vanilla flavor has become ubiquitous with common (we even use it to describe anything bland or basic, i.e. Vanilla is the world’s most popular flavor, from ice cream to fragrances.Īt its most basic sense, Vanilla flavor comes from the vanilla bean.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)